Nice For What?

Tales of a well-adjusted woman

I’ve always described myself as a bitch. Not in any derogatory sense or as a way to put myself down, but as a loving expression of my firmness and adoration of boundaries. I’m a bitch because: I stand up for myself, I leave dates early, I quit my job if I feel disrespected. I’m a bitch because I make my opinions known no matter who they upset even if it means I end up alone (as I so often have). I’m sure that’s not the reclamation of the word other women, especially those older than me, would enjoy being made aware of, but it’s always felt like an apt description of myself. Except that, at some point along the way of my early to mid and now late twenties, I’ve stopped being a bitch, instead I’ve transmuated my personality into that of a ‘nice person’. You may be thinking, “Okay well you were a bitch and now you’re nice, that doesn’t sound too bad? You just learnt some manners, that's all!” However, being nice and engaging in niceness is a trap—sickly sweet and intended to undermine my humanity at every turn.

My niceness, which I view as distinctly separate from my kindness (freely given without expecting anything in return), has left me unable to speak up for myself, which might seem ironic considering I am currently writing this essay for my Substack. I have a voice, a platform, hell, I even have an agent ready to disseminate my work whenever I see fit to get out of my writer's block, yet I feel stunted. I started being nice as a way to avoid conflict. Being away from civilisation (London) for two years meant that I became accustomed to a life of distant socialisation where I could be a bitch to no consquence. Nobody’s asking my opinions on nights out or making sly comments towards me because there was quite literally nobody around me at any given time in Aylesbury. I also think it was a course correction, a way of amending my previous self that did the typical London exodus when things became unmanageable. A previous self that was unruly and deemed too sharp to fit into my friend groups of the past. If I wanted friends, I would be amenable, smiley, and most importantly, nice.

Niceness is hollow; it seeks only to reaffirm my placement as an acceptable woman. Niceness is a performative act with the sole purpose of placating and aiding in measures of pretence without one ounce of sincerity. Niceness is a mask I’ve worn since I was a child, precisely because of my gender. It has allowed me to evade the judgmental eyes that wandered over my midriff and automatically measured the fat around my stomach before getting to know me. “She’s fat, yes, but she’s also nice.”

In Niceness, Flattery, and Deceit (2017), Calvin L. Troup & Christina L. McDowell Marinchak argue that the appeal of niceness is not just powerful, but easy. It indicates approval without “ethical commitment, moral support, or personal responsibility”. Niceness fits comfortably with our need to affirm one another rather than be honest about our feelings. Troup and McDowell Marinchak continue, “The affirmation registers with others as approval, but niceness does not and cannot carry any moral valence; it sets affirmation against evaluation.” I’m not just nice, I’m agreeable. I’m malleable, a shape-shifter that avoids scrutiny because I can turn on the charm and make you laugh at the drop of a hat. In one of our recent sessions, my therapist made a comment that shook me to the core as she so often does. She said, "Haaniyah, it feels like you're performing for me out of a fear you'll be judged. You come in here with stories and your charm as a way to avoid the hard stuff." I immediately felt shame crawl over my face, heating my cheeks to such a degree than she could've easily seen it over the shaky Zoom camera. She was right—I was so committed to putting on a performance that it even crossed over to therapy, the one place on Earth where I'm meant to be the most honest version of myself.

If this is how I act with my therapist, then my god, how do I act with my friends, my colleagues, my family, and, unfortunately, men? I wonder if being nice makes the pill of getting to know me go down easier. You no longer need to wonder if I’m pretty enough, if my body looks right or if I’m intelligent because I’m a “nice girl”. Nice girls eventually become nice women, and nice women don’t protest when you upset them, because, god forbid, I stand up for myself. Nice women don’t make faces of distress because what if someone else feels uncomfortable as a result of my discomfort? Nice women are meek, annoying, push-overs, prudes, cowards, treated like idiots and vapid creatures with nothing but rocks in between our ears. I know this because I’ve spent the past year being a nice woman.

I’ve found that men, in particular, hate nice women. They enjoy being around us because they feel validated by being around someone who feels much too uncomfortable to do anything other than smile when confronted with a gut feeling of emotional dysregulation. Yet, there’s a level of dehumanisation ready and waiting at the door because you’ve shown yourself to be nice. “Haaniyah’s nice, she can take a joke”, “Haaniyah’s well adjusted,” “Haaniyah’s just a great laugh”. And honestly, it is my fault. I smile and laugh at jabs pointed towards me because if I don’t then I’m a shrew that can’t take a joke. I push down my gnawing feeling that something is wrong because surely I’m just reading into how I feel and putting words into their poison-laced mouths. Instead, I bite my tongue, choose to enjoy my time out with friends and go home having had my self-esteem ripped apart seven ways to Sunday. If I don’t, I’m the spoilsport. Didn’t you know, men are just like that! They’re just mean, rude, vicious, pointed, unkind, cruel and most importantly, they’re just men! I wonder if I were a man, if I’d spend so much of my time thinking about how nice I am. Maybe, I’d be a gigantic asshole as so many of them often are. Perhaps I’d single women out based on how attractive I found them and lock them into cages of expectations that they can never escape from. Women doomed to be typecast as fuckable, mean, nice, pretty, and other. You're the Madonna or you're the whore and maybe a secret third thing Freud was too high on cocaine to figure out. I’m nice so that I can escape the other, but I’m finding that my attempts seem futile. I continue to be bothered.

In her 1977 essay “Nice Girl”: Social Control of Women Through a Value Construct, academic Greer Letton Fox suggests that the application of niceness is attached to behaviour and not the individual. Niceness in women is continuously in flux because it’s a never-ending endeavour to ensure that our identities aren’t in jeopardy. Fox explains, “One is under pressure to demonstrate one's niceness anew by one's behavior in each instance of social interaction. In sum, the lady is always in a state of becoming: one acts like a lady, one attempts to be a lady, but one never is a lady. In effect, then, throughout her lifetime, a woman's behavior will reflect continued efforts to attain what is an essentially unattainable status.”

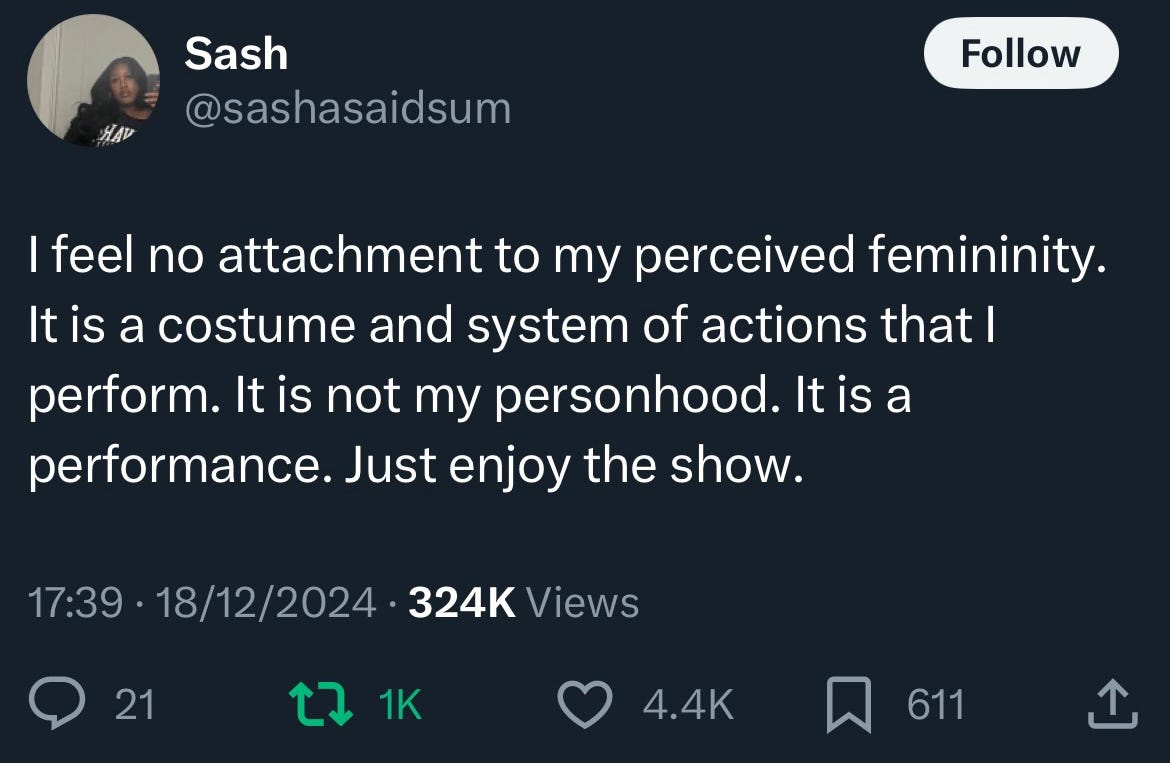

Unattainable status rings around in my head like the auditory remnants of a gunshot. It puts into words a feeling that’s been consuming my thoughts and body since I was able to realise that I was not just a girl, but a fat Black girl. It also reminds me of a tweet that’s been stuck in my head for the past six months (which rarely happens on Elon Musk’s far-right hellhole). The tweet reads:

“I feel no attachment to my perceived femininity. It is a costume and a system of actions that I perform. It is not my personhood. It is a performance. Just enjoy the show.”

When the Barbie movie emerged in 2023, the word girl took over social media. It was girl math, then girl dinner and eventually TikTok videos simplifying politics to explain to the girls. There was a demand to ditch adulthood and fall back into the naivety of not just childhood but girlhood. I found the trend to be unrelatable but also deeply unnerving. I wasn’t sure at the time if that unnerving feeling came from a place of annoyance or actual unease at being reminded of my girlhood without the £15 fee I pay my therapist. I wondered if something was wrong with me—it seemed like everyone else could sit around, share stories of what it was like being a young girl without feeling an immediate sense of doom. Had my bitchiness gone too far into fully formed cynicism preventing me from enaging with human connection? I think about my girlhood (or childhood as I prefer), and I think of a young girl ostracised from the moment she could speak. I think of a girl robbed of the chance to be anything other than chubby, with her future weight at the forefront of her parents' minds rather than her future career. Please don’t take this as a dismantling of my relationship with my mum, who long before she passed reckoned with the damage I was left to deal with or my relationship with my father, whom I love dearly but currently exists as a quasi-bargaining process between us to put aside our eerily similar egos. I think, for as much as my parents failed me, they, in turn, were failed by society, which doesn’t alter history or erase the pain I experienced, but allows me to process it in a healthier way than screaming into my pillow as I often did at 15. My parents instilled in me kindness, care for others, loyalty, and determination to be a good person. Yet, they also did little to prevent growing knowledge from creeping into my brain as a pre-teen that I would never be seen as a girl or a woman, or even a human being. So, how was I to cope? I learnt to be nice.

In the same way, I became nice again as an adult because I wanted friends—I initially became nice as a child as a form of self-protection. I was isolated and quiet, and I made very little noise or waves in an attempt to veer suspicious eyes away from my being. The only thing people could say about me was “She’s a bit weird/quiet/quirky, but she’s nice!”, just as I wanted them to do. I spent my days buried in books, which became fanfiction, cultural criticism in the form of tweets, and eventually writing my articles as a journalist. As I grew, my niceness adapted to my surroundings in the same way Venom protects (and mutates) Tom Hardy from Riz Ahmed or whatever weird villain thing exists, in what I’m going to say seems like a money laundering scheme from Sony. It became a defensive shield I could fall back into if life became too hard. I found myself unable to be honest—fearful of what that honesty would mean. Further explained in their paper, Troup and McDowell Marinchak state: “The fact that we have internalised niceness as a society means that most people take for granted an entire virtue structure that makes “being nice” the primary guide for our public conduct, particularly conversation. Niceness functions as an unquestionable, unscrutinised norm.”

In laymans terms they mean, we all need to stop pretending to be so fucking nice all the time. Or at least that’s what I took from it. Niceness has been my way of normalising and sanitising the harm that has happened to me. It allowed me to make sense and accept that there were ways that I could conduct myself so as not to be targeted for my weight, race, gender and the messy combination of all three. I believed there was some way I could be accepted enough that my personhood would shine through instead of everything else. There's just one problem: it doesn't work that way! Bigotry doesn’t respond to niceness—it doesn’t care how sweet you are or how much you try to woo people to like you. It’s even worse when the bigotry is covert and based on socialised bias rather than outwardly malicious. Men, even, allegedly well-spoken, educated, socially aware men won’t call you a fat bitch, instead they make you feel like a creep for engaging in basic facets of human connection. They placate you, mock you, belittle you, and wrap it all up in a bow, saying, “You’re just so nice!” along with an aloof yet condescending smile. He does it under the cover of one-on-one conversations, not to be caught out by other women who fit into the favoured typecast he has placed them in. It's happened to me as a teenager, a university student, at my first job, and now as a woman three years away from turning 30. My life has been a never-ending cycle of finding myself in the crosshairs of men who see me as an easy target and believe nobody will come to my defence. It’s violence without the receipts to prove said violence, and you feel like a crazy woman for thinking you’ve just been taken for the biggest mug in the world. Nobody else sees this? Nobody else admits there’s an issue here? Am I the problem? So you go home with a sickness that has been transferred onto you by someone unwilling to take the time to heal and mend themselves. Their disease becomes your reality, and there is no cure to be found.

In her essay, Fox ponders: “Who gains from the "nice girl" construct?”

I've thought about that question years before I even came across Fox's work, but as I sit here unpacking my particular trauma through an essay some may call vindictive, I'm trying to determine the why rather than the who. Why have I been tying myself into such an unbreakable knot for so many years? In many ways, I am a failure. I have failed by aiding and abetting the nice girl construct. I have felt it tightening around my ankles for a long time, hardening into place as it has done to many other women and doing nothing to chip it away. There must be some way I can break free, some way I can feel the air in my lungs after drowning in both traditional and progressive misogyny. Perhaps the first step is acknowledgement that I am not a nice woman, and indeed no man’s fantasy. I hope that’s enough.

Citations:

Fox, G. L. (1977). “Nice Girl”: Social Control of Women through a Value Construct. Signs, 2(4), 805–817. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173211

Troup, C. L., & McDowell Marinchak, C. L. (2017). Niceness, Flattery, and Deceit. Western Journal of Communication, 82(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2017.1306097

amazing piece haaniyah. one of the best i’ve read on this app so far.