The Summer I 'Quit' Makeup

on knowing the difference between good aesthetics and good politics

I. 2025

I feel I have failed at being a woman.

Something I’ve noticed in women my age—that being anyone between twenty-five and thirty—is an air of slouchiness. Their clothes are sized two sizes up from standard fit, falling off their shoulders and hips without looking like they’re wearing an ill-fitted costume. It all seems effortless. Sometimes they’re creative types with a knack for styling themselves for their field of choice. Or they’re hybrids of model/bartender or photographer/administrator, who prove that even in their normie jobs, late-stage capitalism’s financial suffocation is no match for a stellar Pinterest board. And occasionally, they’re not creative at all, but they just get it. Doctors wearing Damson Madder, teachers donning Jacob Eldordi’s Bottega bag (scored during a Vinted bid), and bankers wearing purposefully beat-up Mexico ’66s. It’s as if they’re all speaking the same language.

I must’ve misplaced my dictionary.

You’d assume that all these women are skinny, but more often than not, I find myself envying women with body types similar to mine. Despite our physical likenesses, there’s something about slouchiness that eludes me. Not just in the sense that when I wear slouchy clothing I tap into a strange sense of discomfort at being seen as bigger than I am, but that I’m wearing my shame on my sleeve. Hiding rather than making a deliberate fashion choice. It doesn’t help that my boobs prevent me from reaching that end goal of slouchiness. No matter how hard I try, they turn my attempt at slouchiness into clinginess. The uncaring chic into a desperate attempt for attention, which might say a lot more about how I was socialised to view not just my body but women’s bodies in general. Clothing is tight and sexualised, no matter how much I lean into de-gendering myself. I peruse thrift shops looking for men’s jumpers, hoping that this one might allow me to walk around without the immediate glare of voyeurs. That men twice or three times my age will stop leering at me in the same way they leered at me aged fourteen. If an abaya couldn’t stop the leering, how would a 4x sweater sourced from the back of a Cancer Research store fare any better? I’m also considerably bigger than I was as a teenager, a byproduct of grief, PCOS and a fluctuating grip on my sense of self. With that, I’ve had to shift not only my physicality of dressing but mentally alter how I perceive how I’m being perceived. I’m the voyeur in my own head, ala that Tumblr famous Margaret Atwood quote, “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman”.

My shame travelled 3,585 miles with me to Canada this summer. Stored in my overhead compartment, it braved the sudden jerks and sways of a not-so-subtle, terrible landing, determined to claw away at my sense of self even if there was no self to tear down. I landed an hour before my Swedish cousins, who were making a similar trek from Europe to North America, giving me ample time to sit down in the tepid humidity of Toronto Pearson airport. As I watched my fellow travellers meet their families and embrace their lovers, I wondered how I’d adjust to Canada and its distinctly limited public transport. I wondered if I packed enough clothes. Had my aunt gotten the lactose-free milk I asked for? And then, entirely at random, I thought about my recent weight gain. Would it be an issue? Would my aunts and uncles, whom I hadn’t seen since my mother’s funeral two years ago, be upset that I hadn’t lost weight?

I’d just come off one of the worst flights of my life, I was in a new country, and this was the thought that concerned me.

How sad.

I’ve become slightly narcissistic. Not clinically, and certainly not in the way the term is thrown around in our cultural lexicon, deeming any questionable behaviour beyond redemption. But there is a narcissistic quality in my self-loathing. What does my family think of me? What do my friends think of me? What does this stranger on the bus think of me? It’s a futile form of self-obsession. It’s funny that then, on my trip, I made the choice to give up makeup. I told myself this was feminist and self-liberating, thinking about the beauty industry’s ills and my despair at my lone brush with walking around on a 30-degree day in downtown Toronto. After the sickly texture of sweat mixed with foundation flooded down my face, I binned most of my routine, keeping the key essentials: blush, mascara, eyebrow gel, and lipliner. It wasn’t a capital Q quit, more like a silent one. I was doing no-makeup-makeup—Alicia Keys —but broke.

I did feel better about myself. Not because I wasn’t wearing makeup, but because I felt beautiful. For the first time in a long time, I genuinely believed people when they told me I looked good and wondered why I’d been lying to myself for years about how much makeup I needed. When I spoke to my friend Charlie about this, they recounted their own experience of giving up makeup. “Not good politics, but good aesthetics”, they said. Not only did Charlie’s skin clear up, but their bare lashes grew considerably, a natural version of what they’d chosen to give up in the first place. If a feminist or political choice inadvertently brings you the rewards of Beauty or desirability, does that then sabotage your efforts? What if the sabotage can only be felt internally? When I returned from Canada, I continued my pared-down routine, wanting to feel as good as I felt up North. But slowly and surely, that shame crept back in. In conversations, my attention drifted to whether my cream blush had faded or if my beauty store lipliner looked wonky, veering away from the topic at hand and falling headfirst into a pond of ice-cold vanity.

I’m twenty-seven, three years from thirty, and eight years past being a teenager: far too old to be this self-obsessed and far too young to hate myself so much.

At what age do you stop being obsessed with looks, or more importantly, at what age do you stop caring about how your looks influence the way you’re treated?

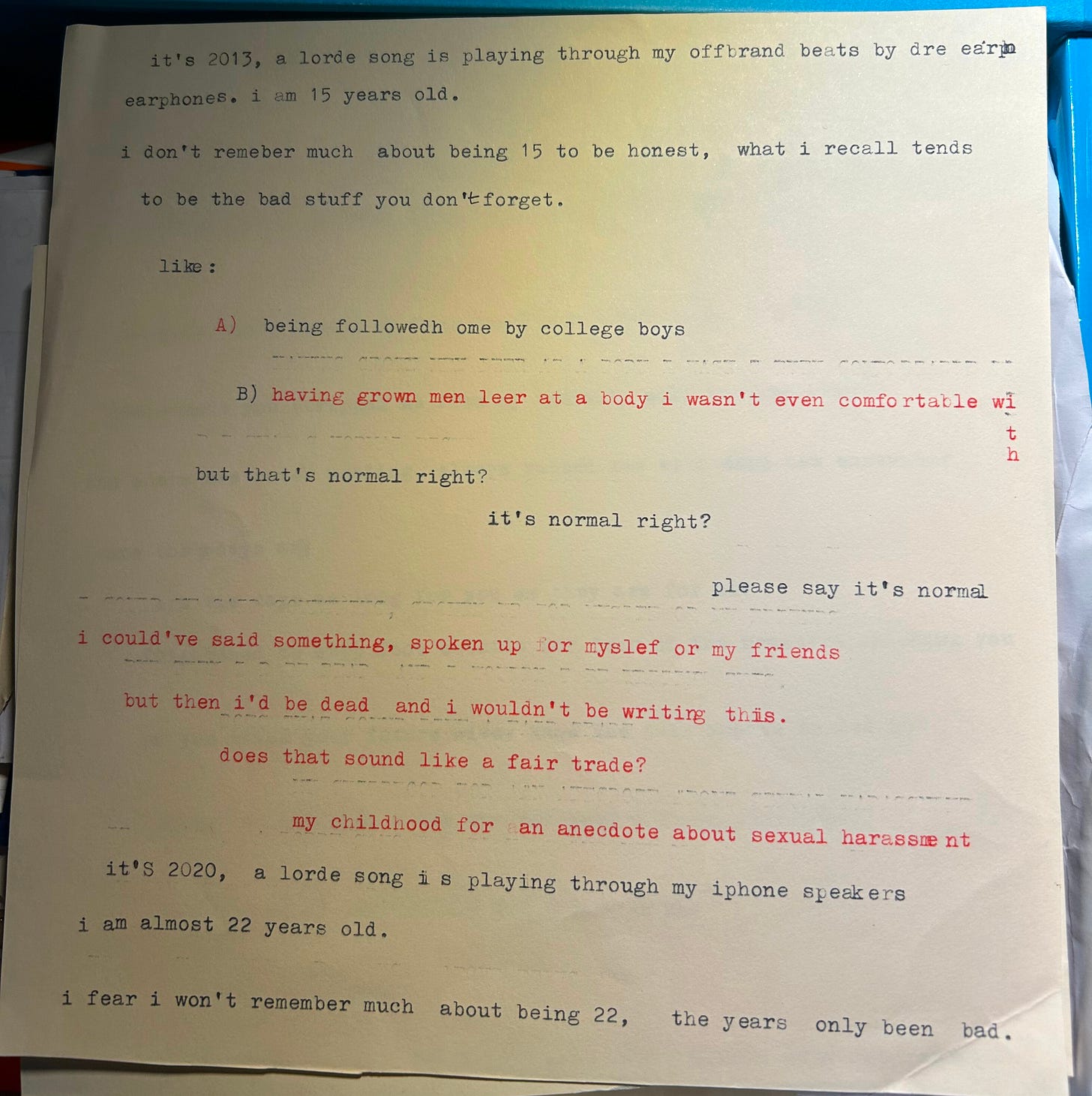

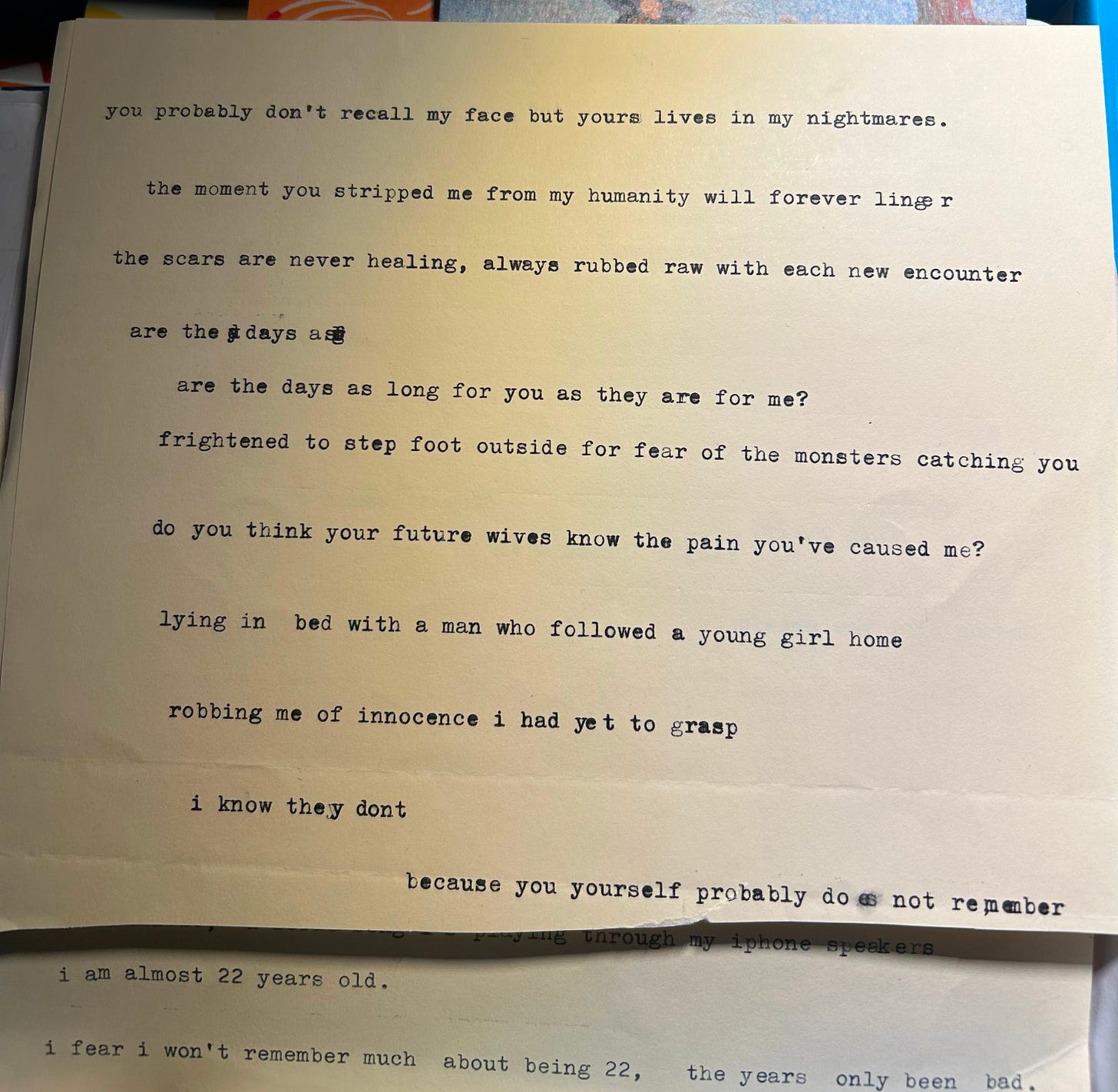

II. 2012

I have a vivid memory of being fourteen.

I’m sitting on the stairs in the old house I grew up in. The faint outline of my mother yells at me to hurry up and wash my face before my grandmother comes to pick me up for secondary school. She, or the blurry figure in her place, insists that the makeup thrown on my face at the crack of dawn makes me look like a clown. Harsh to hear, but she’s right. I do look like a clown, made up with dark, streaky bronzer stolen from her bedside drawers, fuchsia-pink blush, and shimmery Dior eyeshadow gifted by my aunt after her time as a House of Fraser makeup artist. It sits on my face like costume paint, rather than carefully applied to fit my features. I argue back, like any teenager brimming with hormones and insecurity would. Why is she ruining my life? This is how all the girls do their makeup! Why can’t I be like them?

My mother doesn’t give in to my pleading; she didn’t wear makeup at my age, so why should I? More importantly, I am already naturally beautiful. I roll my eyes at her. Naturally beautiful is something you say to make ugly girls feel better about themselves, and I already know I’m deemed ugly; I just want a way to fix that. After some umming and ahhing, I acquiesce. I wash my face and slide into the backseat of my grandmother’s small Toyota, mentally preparing myself for the day ahead. I wish I could physically link our brains so she would know the pain I’m in. I can’t explain why I so desperately need makeup, but in my bravest daydreams, I confess to her, “Mum, I feel ugly” or “the boys in school make fun of me for being fat”. At times, I feel it at the tip of my tongue, and yet I hold back with the knowledge that this level of honesty had been hammered out of me after one too many times complaining about my insecurities.

I was also fourteen the first time I was sexually harassed. After weeks of comments about my boobs and my bum, both of which developed early, a boy groped me after our English class. It was on our way to our DT department. I felt a hand grab and squeeze me from behind, and a chorus of laughter followed shortly after. The other boys wondered why I was covering up when they could see the outline of my figure, suggested I might as well take my hijab off, and that because I was chubby, there was only one use for me. All, of course, ramblings of insecure, childish teenagers, but the feeling that I must compensate for a perceived lack took root on that day—poisoning me from the inside out. Later, one of those same boys snatched my hijab off my head in an RE class. I was angry, but I also wondered if they might have treated me differently if they had considered me attractive. This was the lesson I could learn: becoming more attractive might prevent other boys or men from treating me like that.

As an adult, I can look back and realise that my child self was making sense of inexcusable actions. The idea that looking presentable can protect you from harassment is a myth. As writer and educator Mia Mingus argues in her keynote speech Moving Toward the Ugly: A Politic Beyond Desirability, there’s an illusory solace in beauty. That the idea it can protect you is a farce, because “if age and disability teach us anything, it is that investing in beauty will never set us free. It has always taken the form of an exclusive club, and supposed protection against violence, isolation and pain, but this is a myth. It is not true, even for those accepted into the club.” But try explaining that to a fourteen-year-old. The constant belittling from boys whose approval I so desperately wanted to win meant there was no logic-ing my way out of it. If I accepted that there was nothing that could be done to prevent harassment and violence, then it would mean I’d be prey for the rest of my life, and wouldn’t that be tragic?

III. 2015

I also remember being sixteen. The only things that kept me afloat during my tedious IGCSE exam prep were: my dying K-POP phase, my DC Comics obsession, several TV shows (BoJack Horseman, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and The Mindy Project), and makeup. The makeup routine I had at sixteen was in no way unique to me; I was one of many caught up in the onslaught of Instagram makeup tutorials and the peak of MUA Influencer culture. This routine became my weekly treat, similar to that of the weekly cheat day I had after a gruelling five days of working out and strict dieting. Looking back, it was clear that my way of avoiding the mistakes of 2012 was to exert extreme control over myself and my appearance.

Attending a religious girls’ school in Saudi Arabia meant makeup was forbidden during the week. My high school’s military-like standards of ‘cleanliness’ were so strict that on one of the few occasions I wore mascara, I was called out by my biology teacher, who asked if I was trying to impress a boy during school pick-ups, the only time our gender segregated school allowed us to mix with teenage boys. I turned a deep red, laden with embarrassment at being singled out because I wanted to look as pretty as I thought my classmates did, most of whom were non-Black, lighter than I and much slimmer. It was only at the end of the school week that I could sit at my altar, my bedroom desk transformed into an MUA table, holding the weight of all my pots and potions. I spent hours learning how to cover every spot, smooth out my skin texture, and practice the sharp edges of liquid eyeliner until my eyes began to sting from the makeup wipes. I wanted to be pretty because pretty girls were treated better. I savoured my time walking around the local park and in malls dotted close to my compound, my face adorned with the latest beauty technique from a tutorial logged in my YouTube Watch Later. Except in my case, Anastasia Beverley Hills was substituted for drugstore makeup products, which my father bought at my behest instead of the books I used to ask for at thirteen, the last year I recall being makeup-free.

When I visited my father in Saudi Arabia this past March, I got coffee with a childhood friend. We caught up on the last couple of years and the changes in our lives since we last saw each other in 2022. At a certain point, I brought up just how terrible our experiences of sexual harassment in public spaces were. When she reacted with confusion, I reminded her of a lane next to our houses known as ‘rape alley’ where girls our age were frightened of ending up after dark. Her confusion and subsequent dismissal of this—an attitude of ‘oh well, you know kids’—brought me a feeling of unease, not about her judgement, but at my own. Was I making too much of this shared experience? Did I allow these men to cloud my fond memories of growing up, or had I just experienced something different from them—a harassment tinged with fetishism for my Blackness and larger body?

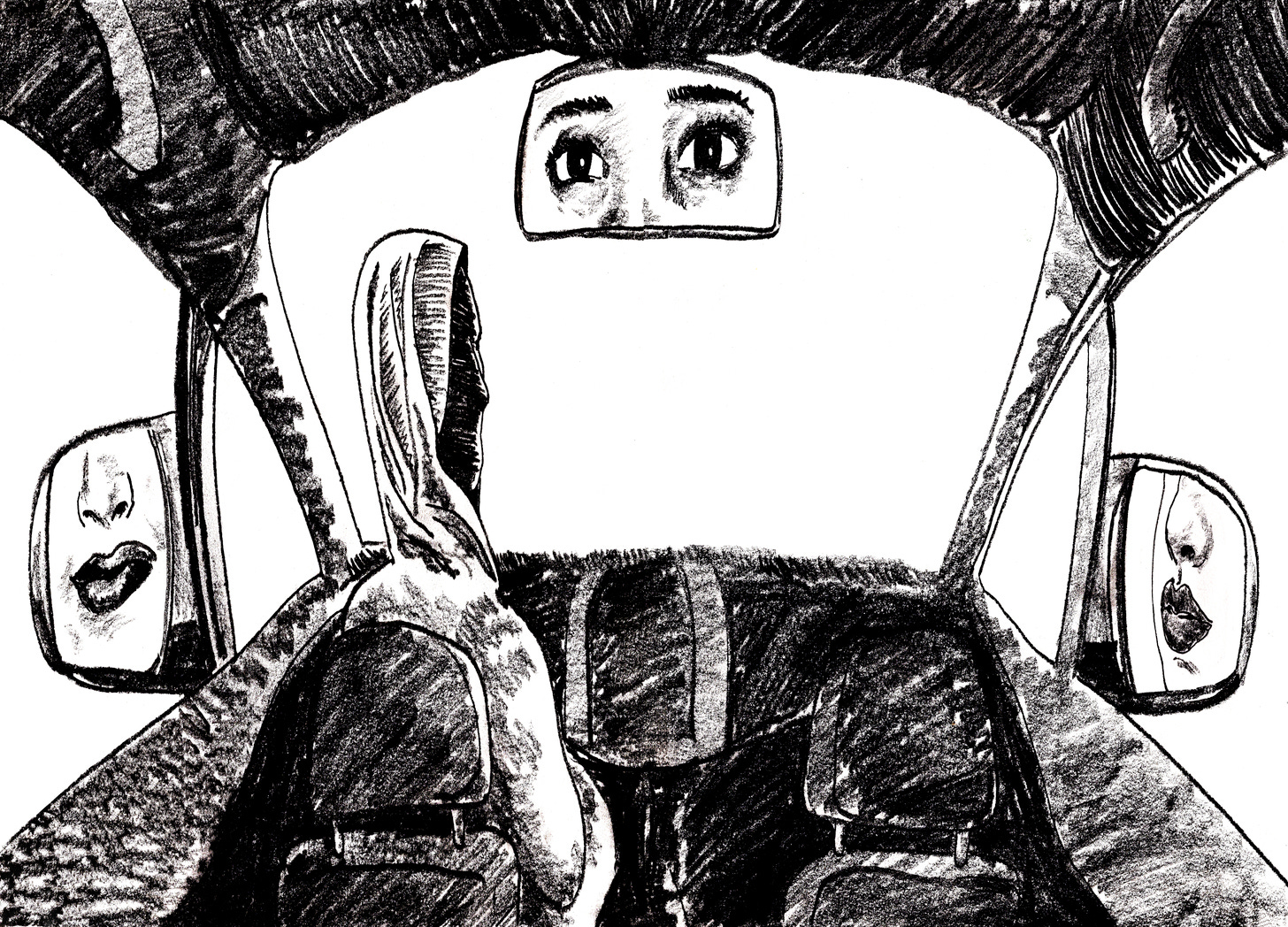

On several occasions, I was followed home by college-aged boys who resided in on-campus dormitories inside the compound. Sometimes men made comments about my makeup, suggesting my red lipstick was sexy and wondering how old I was. Once, a group of men in a SUV stalked me as I walked my usual routine after dinner, only leaving me alone after I went up to a stranger with her baby and asked her to pretend we knew each other until they left. I was catcalled from car windows, profanities such as sharmouta (whore) thrown my way for wearing a coloured abaya or playing around with my style of hijab. Eyes leered at me everywhere I went, perpetual staring that always went down to my hope half or bottom, despite the fact that I was covered head to toe. I complained to my parents about how unsafe I felt. Possibly, I was just more sensitive about it, as I tend to be with everything in my life, but living on the edge became unsustainable. I was a shell of myself, unsure of where I, Haaniyah the girl, began and where the apparent desire of my body from unwanted glances ended.

When I experience sexual harassment today, I simply blankly stare at the perpetrator and walk off. If I’m feeling brave, I tell the man to leave me alone. But there are days it gets to me: recently, a man cornered me near my flat, confessing he’d never slept with a fat woman before (he used a much lewder term). Our both being Somali meant that we already had a shared connection, he said. He told me to get into his broken-down car, and after saying no several times over and over again, I rushed home and cried in my bedroom, partly scared that he might’ve followed me and knew where I lived, and partly confused about why I couldn’t prevent this. I was wearing my Tony Sporano fit (baggy shirt with a tee underneath), I had no makeup on, and my hair was a few days past wash day. I hadn’t allowed him to find me attractive, so why was he still determined to do so?

I wish I had a switch to make me invisible, to dull down any part of me that a man might pester me about.

Back at home, I cursed myself for having a body in the first place. I brought this on myself for not covering enough, for daring to exist in public at all. I reverted to my fourteen-year-old self, wondering if I could prevent this by losing weight, because that would mean my boobs would shrink. If there were less of me, then I’d be less visible to men. I knew this strategy didn’t help me avoid lingering gazes at sixteen, but for those few moments, it gave me comfort.

IV. 2025

I travelled to Canada in late June. My aunt, whom I’ll refer to as mamo, lives in Milton, ON, a small town outside of Toronto. There were seven of us in the house: my mamo, her two sons, her husband, my cousins from Sweden and me. This marked the first time I saw my mum’s family since her funeral in 2023, and the first time in three years I left the country for a holiday. Saudi Arabia didn’t count. Canada felt familiar to me, given the dominance of North American culture I remembered from my childhood in the Gulf. The only difference was the fresh air, gorgeous green landscapes, and cul-de-sac houses, which reminded me of Gilmore Girls’ Stars Hollow. For those two weeks, I was in a different country; cars drove on the opposite side of the road, and the food was both unduly sweet and extraordinarily salty. But I was also different during that trip; something in my life paused and reset in a way I haven’t yet named. Maybe it was spending time around my loved ones, microdosing the familial structure I so desperately needed. Nobody tells you when your mum dies that your family unit is most certainly going with her.

I spent most of my time traversing Plazas. My mamo reminded me of the distinct difference between what Americans call strip malls and the fancier architecture of these buildings. I went to her favourite restaurants and spent days sightseeing in nearby small cities, including a visit to Niagara Falls. I was a tourist, and admittedly, tourism is fun. That aforementioned shame petered out over the first few days of my visit, around the time I decided to cut down on my makeup. On the third or fourth day of my trip, I abandoned my foundation. It was sweltering, and sick of wiping the sweat off my face, I decided to stick to the basics. I made one change, slightly overlining my lips to give me a fuller look. I went out and immediately noticed a difference. There weren’t hordes of people coming up to me or calling me pretty (though my mamo did every day), but I felt like an adult. That condensed routine made me feel attractive in a way I hadn’t felt in years, if ever. In the mirror, I no longer saw that fourteen-year-old, trying on her mother and aunties’ makeup to cover something up—I saw myself as I am right now. It seemed like such a minuscule thing to have such an impact, but through the holiday, I kept to this new routine, and I felt unbelievable. Charlie was right: it was about good aesthetics, certainly not good politics.

The makeup routine I’d developed as a teenager in 2014 & perfected in 2015 coincided with my flirtation with feminism. I, like many of my friends in their mid to late twenties, was very online, and my learning of basic political knowledge came from the internet. I watched video essays on the wage gap, read Tumblr posts that waxed lyrical about body hair and the shame around it, and I became aware of the pink tax and the sheer amount of money spent on the beauty industry. Pop feminism was also taking root around this time. Beyonce stood on stage with the word ‘feminist’ written behind her in bold font, and, in a similar vein, actors like Emma Watson and musicians such as Taylor Swift and Lorde were proud and loud about their feminist journeys. Here I was, a teenage girl utterly depowered by the amount of harassment I was experiencing, not to mention casual racism by classmates and friends alike, but online, this world and outlook made sense to me. Of course, since then, my understanding of feminism as a political framework has developed, especially after discovering the likes of Audre Lorde and Angela Davis in my late teens, but the pop feminism that initially educated me has since degraded into a rehash of the worst of 2000s postfeminism (at least back then it gave us Sex and the City).

To the masses (comment sections): Beauty is a human right. What’s the point of making yourself feel or look ugly when the world is already so complicated for women? They deserve to feel attractive, loved, hot, and sexy because it makes them feel good about themselves. Isn’t feeling good about yourself feminist? Isn’t that precisely what we’ve all been lambasting each other (and the world) over? Feeling good about oneself, putting pleasure over hardship, and happiness over discomfort? Unfortunately, despite its absurdity, I do suspect that this plague has struck me. I realise that I, too, have been treating Beauty as an inalienable right that I validate through self-help rhetoric. I must be exhibiting self-love because I look good, right? I know I tell everyone I don’t care about looks and that we must dismantle Beauty, but when it comes to myself, that same belief system doesn’t apply. I was a great faker, but inside, I felt myself die a little more each day.

For a few months after I left Canada, “good aesthetics, not good politics” became the troubling motto for my relationship with makeup and beauty. I feel more attractive now, so I should be more attractive. I noticed an ease in the way I’d talk to people; instead of being wracked with nerves, I made direct eye contact, smiling wider and laughing with more fervour than ever before. But if using makeup to alter how I was perceived once made me feel alien, then giving it up brought on a slow unease about how naturally attractive I should be. Was my skin good enough? What about my teeth? Do my eyes look weird? Maybe they’ve finally clocked onto the lack of symmetry in my face! Or perhaps I’m just thinking about myself too much, as Jemima Kirke once said when asked “what advice she had for unconfident young women”.

Halima Jibril expressed a similar sentiment in her essay My year of divesting from beauty culture. For Halima, detaching herself from the importance of beauty was difficult. Describing it as Beauty noise (à la food noise, something I know all too well), she argues that discourse about optimising our appearance is inescapable. Halima told me that a photo of her from a friend’s party inspired her to write the piece, one she disliked but didn’t cause her to spiral in the way she would’ve before her divestment. It’s not that Halima doesn’t care, but she now understands that this care isn’t about what’s good for her; it’s more about what she feels she’s meant to be doing as a woman rather than what she wants to do. I understand where Halima is coming from. In September, the second anniversary of my mum’s passing coincided with one of the most significant career opportunities of my life so far: a live Q&A with the BFI1. A horror story if you’ve ever heard it. How was I meant to pay attention to the people in front of me when all I could think about was the fact that my mum died two years ago today? But I wasn’t really thinking about my mum, as bad as that may sound. Messages from friends, flowers, and a visit from my nan were all support that underscored the tragedy of what the day was. Yet, I didn’t cry; bolts of nerves sparked up and down my body as I imagined falling over in front of 400 people. I thought about my questions over and over, considering how confident my voice would sound across the microphones and whether I would correctly pronounce the names of the cast and crew.

What I wasn’t thinking about that day was my body or my face. Amidst all the drama, joy, heartache, and pride, the one feeling that didn’t rear its head at all was insecurity. I’m not sure why, on that day of all days, it suddenly clicked that I was allowed not to care about how I looked. Perhaps it was the remembrance of death. That I was here on this stage was a testament to the hard work I had put in. More important things exist in the limited time we have than looking into a mirror to confirm that your body looks as bad as you feel it does. On my way back home with my grandmother, I pored over the photos sent by various friends and peers, reposting their stories that featured shots of me on stage at angles I’d usually deem unflattering. For the first time in my life, I felt nothing while reposting every single one. Not embarrassment, not annoyance, not regret. I knew this indifference was a temporary feeling, one quickly replaced by a familiar discomfort a few days after, but embracing it, even if only for a day, felt like being allowed to take in a deep breath after holding my head underwater for aeons.

And yet, I still feel that I have failed. At being a woman? Perhaps. At being a fully fleshed out adult? Probably. Moving forward past that feeling of letting my younger self down? Most definitely.

We’re now at the end of the year, only a few weeks away from 2026, but if I’m not careful, the water I’ve been plunging my head into might begin to freeze over, keeping me stuck in the cycle of push and pull, of self-hate and self-obsession. When walking home last month from a late screening of Die My Love (2025), I vowed to do three things: be kinder to myself, make healthier choices, and be more honest with myself. I usually make these vows or promises to myself after an ADHD-related meltdown, but this latest addendum to my plan for adulthood was brought on by my birthday. I desperately want to rid myself of the feeling of failure, to prove I’m not a bad friend, writer, employee, random IG mutual you never talk to but always watch the story of. I want to feel beautiful and loved, not just because I know the world is unjust towards those considered ugly, but because the fourteen and sixteen-year-old versions of myself are still somewhere deep down, and their need for validation far surpasses mine.

I know that my being fat and subsequent experience of fatphobia is a systemic and long-term issue which impacts the way I’m treated at the doctor’s office, or when looking for work or how people see me as someone worth caring about. I should be okay with being overlooked, judged or ridiculed. I should be mature enough to accept that the world might not get to a place of neutrality, but I don’t think I ever will be. I want to make choices about myself that are rational and driven by good politics, but in all actuality, they aren’t. My aesthetics won’t better the world or make a change for others, but what it will do is make the fourteen and sixteen-year-old inside of me stop feeling shitty. Because maybe if they stop feeling shitty, then grown-up me can stop feeling shitty. It’s selfish, but I am an imperfect person still learning how to feel safe again. And until then, or at least until I find an Imam ready to exorcise those teenage selves, all I can do is quiet their insecurity. So for now, I’ll be getting a one-way ticket to Vanity Junction.

Thank you once again to my editor, Emma Tranter. You make all my words make sense!

Also, a massive thank you to Ned Knight for illustrating this essay!

British Film Institute